China's devaluation is an effort to stimulate an economy that is growing less rapidly than its potential. China is not in recession—probably—but its growth rate has certainly slowed. The devaluation will help, but don't expect any immediate miracles.

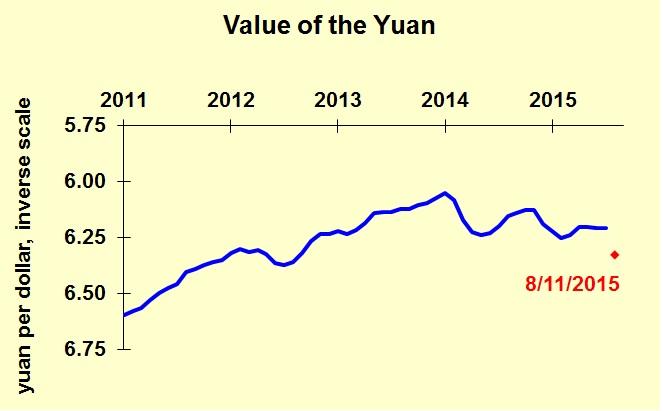

The official statement from the People's Bank of China reads like something Alan Greenspan might have written. The gist is that they will let the yuan float against other currencies—maybe. I have my doubts about that. Monday's move was large for a daily change, but does not take the rate outside of the recent trading range.

Exchange rate policy cannot be separate from monetary policy. This is a commonly misunderstood notion. If a country, for example, is running an expansive monetary policy, increasing its money supply and pushing prices up, there is no way it can also push up its currency. If it tries to buy its currency using foreign exchange reserves, it is tightening monetary policy. There is really just one policy. China's economic leaders may not understand this. (The United States has had a number of Treasury secretaries who didn't understand it.)

Expansionary monetary policy may help China's economy accelerate. A declining exchange rate is one of the mechanisms whereby monetary policy helps the economy, but not the only one. As the exchange rate falls, the country's exports become cheaper to foreigners, increasing sales volumes. Imports become more expensive to the country's citizens, encouraging them to shift to domestically manufactured goods. So it's a helpful policy.

How much help does China's economy need? That's hard to say, given the sorry state of economic statistics. The GDP growth rates that are reported by the National Bureau of Statistics of China are unreliable. The recent four-quarter growth rates are far more stable than any period we have seen in the United States, meaning either their economy is far more stable than ours, or their statisticians are far more pliable. The reliable indicators we have suggest weakness but not an actual decline in the Chinese economy. U.S. exports to China, for example, have increased by 3.8 percent over the past 12 months, compared to a long-run average of 11 percent annual growth.